A brief history of Coleford

The historic market town of Coleford lies in the centre of the Forest of Dean in Gloucestershire, and together with its surrounding villages is home to around 8,500 people. It is also the main shopping centre, and the ideal place from which to explore the stunning scenery of the Forest, and the Wye Valley which it borders.

The Forest of Dean was formerly a Royal Hunting Forest, although the last recorded actual ‘royal’ hunt took place over 700 years ago. The forest continued to supply venison to the royal households for several centuries after that, and the rights to much of the timber were also guarded by the crown. Our fallow deer, and (more recent) wild boar populations, probably feel a bit safer now, although Forestry England does operate an abattoir and, after health checks, sells the meat from culled animals to the trade.

Small beginnings. Coleford’s origins were in the early to mid-13th century, as a tiny settlement around the confluence of three small streams, which joined in the hollow of the surrounding hills. The main water course was Thurstan’s Brook, which rises above Broadwell and flowed via a royal fish pool which gave its name to Poolway. This was joined by the Coller Brook rising near Edenwall to the south east (later giving its name to Coalway), and Sluts Brook, rising from a spring near Crossways to the west. (Source: British History Online). The hamlet grew beside a ford, which allowed the passage of charcoal and ore from the local mines. As a detached part of the parish of Newland, the people of the settlement paid ‘tithes’ to the church there, and used the ‘Church Path’ (sometimes called the ‘burial path’) to get to Newland for worship, or to bury the dead. By the 17th century this had been replaced by a road in the valley of Thurstan’s Brook (now known as Valley Brook).

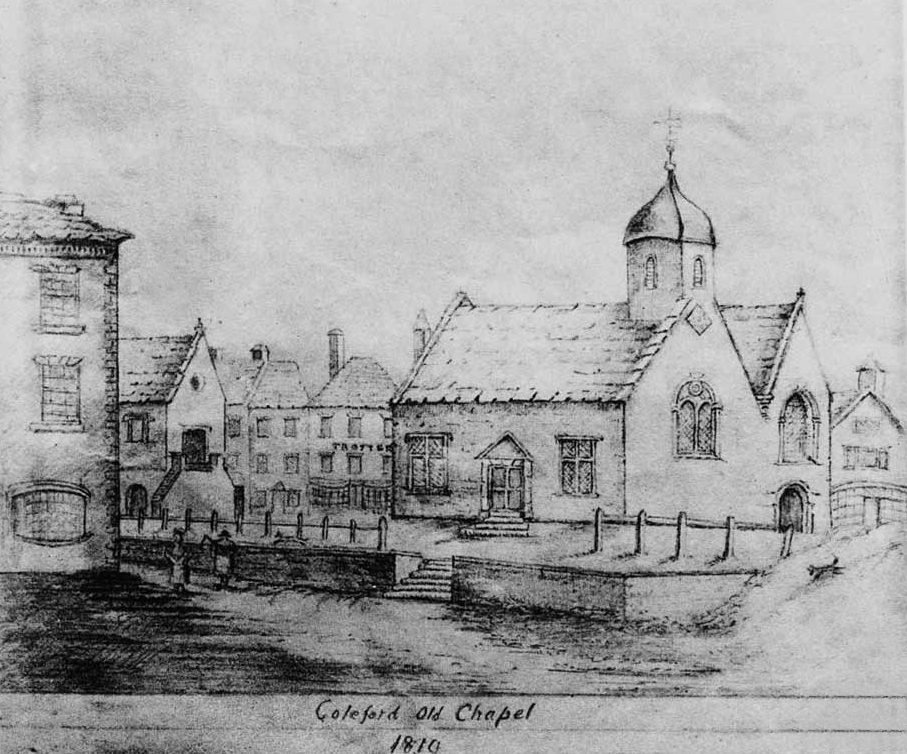

Being in a somewhat strategic position, with many routes converging on it, Coleford grew in size and importance. By 1489 it had its own ‘chapel of ease’, sited where the clock tower and market place are today. This sketch, dated 1810, is by Margaret Mushet, eldest daughter of David Mushet (see below). Its growth continued mostly along the lines of the Gloucester Road and Newland Street, which led to the smaller settlement at Whitecliff. There were also a few houses along what is now St John Street, (then simply known as the Berry Hill road.)

Its growth continued mostly along the lines of the Gloucester Road and Newland Street, which led to the smaller settlement at Whitecliff. There were also a few houses along what is now St John Street, (then simply known as the Berry Hill road.)

Battle of Coleford. During the early stages of the English Civil War, in 1642 the commander of the Parliamentary garrison started a market in the town, as nearby Monmouth was held by Royalists. On 20 February 1643, a Royalist army, consisting of 500 horse and 1500 foot soldiers, marched through Coleford on their way to attack the Parliamentary stronghold at Gloucester. At Coleford they were met by a troop of Parliamentarians aided by a group of Foresters. A three hour battle ensued, during which the market-house was burnt and the church badly damaged. The commander of the Royalists and two other officers were shot dead before the defending force was overcome. Its leaders and about 40 men were captured, and the rest retreated into the surrounding forest. The Royalists continued to Gloucester, where they dug in at Highnam manor. After a fierce battle, in which they were attacked from two sides and 500 Royalists were killed, they ran out of ammunition and were forced to surrender to the Parliamentarians.

Growing prosperity. Following the ‘Restoration’ of the monarchy, in 1661 Coleford was granted a market, providing a major stimulus to the town. A new market house was built in 1679, and within 50 years Coleford had grown to over 160 houses. Of the older surviving buildings in the market place, the Old White Hart Inn dates from the 17th century. In 1820, the old church which had by then fallen into ruin, was rebuilt, and partly funded, by the ‘Perpetual Curate’ Henry Poole, who had practised as an architect before his ordination.  Built in an octagonal form, with a square clock tower at the western end, the church stood for only about 60 years before it proved too small. It was demolished in 1882, and replaced by St John’s, in Boxbush Road, overlooking the town centre. The tower however, was retained as a clock tower, and today it is Coleford’s most iconic feature. The octagonal shape of the old church is outlined with grey bricks, in the paving of the present market place. The market house (or town hall), was rebuilt on a

Built in an octagonal form, with a square clock tower at the western end, the church stood for only about 60 years before it proved too small. It was demolished in 1882, and replaced by St John’s, in Boxbush Road, overlooking the town centre. The tower however, was retained as a clock tower, and today it is Coleford’s most iconic feature. The octagonal shape of the old church is outlined with grey bricks, in the paving of the present market place. The market house (or town hall), was rebuilt on a

Industrialisation. Throughout its history, Coleford has always had a mixed economy based on both agriculture and industry. Its rich mineral resources of iron ore have been exploited since at least 3000 years ago, as the ancient shallow pits known locally as ‘scowles’, testify. The early iron workings though, were not very efficient. Much of the metal was left unrecovered in the form of discarded ‘cinders’ which, over many years, formed huge deposits. By the late 17th century, iron ore mining as such had been abandoned in favour of quarrying the cinder deposits. These continued to be exploited and recycled in the more efficient smelting furnaces built during the industrial revolution of the 18th and 19th centuries, while several new ore mines were also opened. The furnace at Whitecliff which has been conserved, is the only remaining example in southern England of an early coke-fuelled blast furnace.

In 1808, Thomas Halford, the owner of the two furnaces at Whitecliff recruited the Scottish born metallurgist David Mushet, to improve the design of the furnaces. In 1810 Mushet bought Forest House on Cinder Hill, (now an hotel), and moved to Coleford with his family to become full-time manager of these furnaces. Having purchased land at Dark Hill, south of Milkwall, in 1818 he set up a small ironworks of his own, which he later handed on to his youngest son, Robert ‘Forester’ Mushet,  born in Coleford in 1810. In 1856 Robert found a way to improve Henry Bessemer’s steel making process, by adding manganese to the iron ore during smelting. Although the production of steel in the Forest itself was never in large quantities, this high quality steel was particularly suitable for railroad tracks and was exported worldwide. Robert Mushet later developed hardened alloy steels for toolmaking, by adding tungsten and chromium to the steel.

born in Coleford in 1810. In 1856 Robert found a way to improve Henry Bessemer’s steel making process, by adding manganese to the iron ore during smelting. Although the production of steel in the Forest itself was never in large quantities, this high quality steel was particularly suitable for railroad tracks and was exported worldwide. Robert Mushet later developed hardened alloy steels for toolmaking, by adding tungsten and chromium to the steel.

Environmental destruction. Looking at the Forest today, it is almost impossible to believe that just over a century ago, it was a heavily industrialised area. A devastated landscape scarred by mines and pits of all sorts – deep shaft coal mines with winding gear, vast open-cast pits, and drift mines sunk into hillsides where the underlying coal seams were exposed. One of the richest seams was the ‘Coleford High Delf’. A small reminder of this era came in 2016, during the building of the Thurstan’s Rise estate. In the central area, ground-workers hit the ‘Lower Trenchard Coal Seam’, which crosses the site. They dug out about 60 tons of coal – and were promptly told to put it back!

Two huge limestone pits were dug, at Whitecliff (now an ‘off-road activity centre’), and Scowles, near what is now the Stowfield quarry.

Regeneration. Since the end of the 20th century Coleford has redeveloped itself as a centre for tourism, although there is still much light industry in the area, and Forestry England is one of the area’s major employers. Although the Forest of Dean is devoid of natural lakes, a popular recreation area is the Cannop Ponds, which lie just south of the B4226 (Speech House Road) between Coleford and Cinderford, in the valley of the Cannop Brook. The lower pond and a 1.5 mile long ‘leat’, were constructed in 1825, to provide a constant supply to a huge waterwheel, built to power the blast furnace at Parkend ironworks.

Close to these ponds is the Cannop Cycle Centre with its extensive network of forest cycle trails – many using the old railway tracks – and the Forestry England recreation centre at Beechenhurst Lodge.

A short walk from here, past the Speech House Hotel (a former hunting lodge and the headquarters of the Forest of Dean Freeminers) is Woorgreens – another extensive nature reserve, created on the site of what was until the 1950s a vast open-cast coal mine. Jointly managed by Forestry England and the Gloucestershire Wildlife Trust, it has been restored to provide a diverse range of wildlife habitats, including a large shallow lake, coppiced woodland, scrub bush, and open heathland partly maintained through ‘conservation grazing’ by a small herd of highland cattle.

[The three historic images above are reproduced here with the kind permission of Geoff Davis, Sungreen.co.uk. Many thanks Geoff!]